Why do whales sing? How do they do it? Can all whales muster up a melody? Whale songs continue to intrigue and amaze both scientists and the public.

We humans like to think of ourselves as special. It is difficult for us to conceptualize the complexity and intelligence inherent in the natural world and life in general. We often claim to be the sole earthly proprietors of art, language and other forms of advanced creativity. There is no doubt we are an extraordinary feat of evolution, uniquely equipped to dominate our environment, but we are not quite as exceptional as we like to believe. We tend to anthropomorphize everything, which is somewhat understandable considering that we have no reference point beside ourselves. But when we are able to to push aside our biases a more magical and humbling world comes into view.

Take the example of music. A quick Google search for “earliest forms of music” or “history of music“, turns up results that discuss only the history of human music. Dictionary.com defines music as: (1) “An art of sound in time that expresses ideas and emotions in significant forms through the elements of rhythm, melody, harmony, and color. (2) The tones or sounds employed, occurring in single line (melody) or multiple lines (harmony), and sounded or to be sounded by one or more voices or instruments, or both.

There is an incoherence here that displays our condition perfectly. We are able to create detailed words, concepts and definitions to accurately describe our experience of reality. However, we seem unable to comprehend the fact that these same things may apply to beings other than ourselves. Whale songs and other forms of music made by even older species precede us by millions of years.

Cetaceans & sound

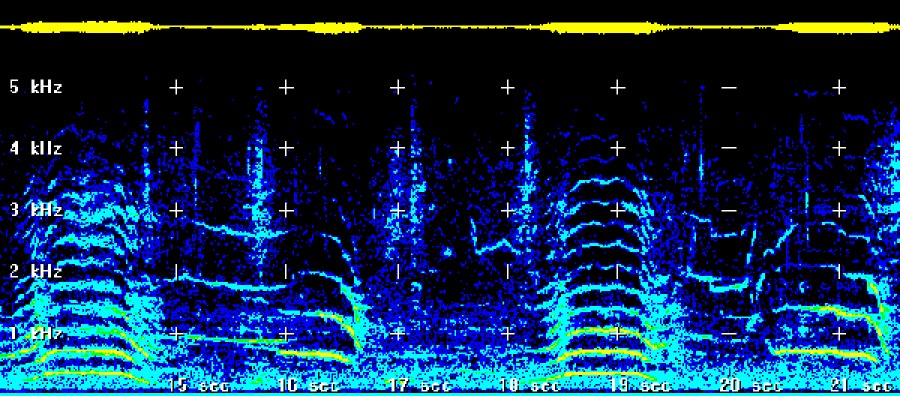

Whales and other Cetaceans use sound in a number of ways and for a variety of reasons. Sperm whales use highly complex biological mechanisms to produce clicking sounds that can be used for hunting, navigation and communication. They are also one of a number of species, including Orcas and Humpback whales, that have culturally unique dialects. Due to the difficulty of seeing in poor visibility or low/no light situations, Cetaceans have evolved to rely more on sound than sight. Factor in an evolutionary journey millions of years longer than our own and it becomes far more than plausible that their mastery of sound is more advanced than our own. This exert from Captain Paul Watson’s essay The Cetacean Brain and Hominid Perceptions of Cetacean Intelligence describes some of the differences in the way Humans and Cetaceans perceive and use sound:

“Sight in humans is a space-oriented distance sense which gives us complex simultaneous information in the form of analog pictures with poor time discrimination. By contrast, our auditory sense has poor space perception but good time discrimination. This results in human languages being comprised of fairly simple sounds arranged in elaborate temporal sequences. The cetacean auditory system is primarily spatial, more like human eyesight, with great diversity of simultaneous information and poor time discrimination. For this reason, dolphin language consists of very complex sounds perceived as a unit. What humans may need hundreds of sounds strung together to communicate, the dolphin may do in one sound. To understand us, they would have to slow down their perception of sounds to an incredibly boring degree. It is for this reason that dolphins respond readily to music. Human music is more in tune with dolphin speech.”

An informative animated TedEd talk on why, how and which whales sing.

Whale songs vs vocalizations

Many Cetaceans and animals in general produce vocalizations, but creating music is another thing entirely. Creating harmony, melody and rhythm requires an advanced intelligence. The ability to remember and add to songs, even those composed by others, is proof of an equally impressive memory. Only a few Cetacean species are known to ‘sing’, all are Baleen whales. They include the Blue, Fin, Humpback, Bowhead and Minke. Of these, only Humpbacks and possibly Bowheads produce sequences long and complex enough to resemble what we consider to be a song. Blue whales produce some of the loudest and lowest frequency sounds on earth, but only males string these sounds together to produce a form of singing. Males vocalize far more than females in general and their songs can travel hundreds of miles underwater, theoretically enabling them to send messages around the globe within hours.

By far the most well studied and best understood (but still quite mysterious) of all whale songs is that of the Humpback. As with all singing whales, the performers are always male. This has led many scientists to believe that the songs are used to attract mates or display dominance. Humpback whale songs are extremely complex and display cultural variation among geographically diverse populations. Each season the males of a particular population will create a new song that all of them sing. As the mating season progresses the song becomes longer and more complicated, with songs lasting between 5 to 30 minutes. Sometimes, males will perform together, while individuals have been known to sing for up to 22 hours straight.

An inspiring animated short film about how the discovery of the Humpback whale song helped

inspire people to better protect whales.

Noise pollution

Whale songs are just a part of the chorus of sounds that create the soundtrack of the seas. We once thought of the ocean as a place of silence, we now know that sound plays a vital role in the lives of many species. Coral reefs buzz, hum and click while Cetaceans fill the open seas with their myriad vocalizations. But today this soundtrack is being drowned out. As we have done with so many aspects of the natural world, humans are interfering with catastrophic consequences. Anthropogenic sounds can be detected throughout the ocean, from shipping traffic in the open seas and tourist boats zipping over reefs to drilling and resource exploration in the most remote corners of the globe.

Naval sonar systems are the most frightening example of our willingness to look the other way when activities we see as beneficial to our own species harm a multitude of others. These devices are used to map the sea floor or locate large objects and the sounds they produce can travel tens or even hundreds of miles, creating deafening noise that is far above what is considered safe for humans. Even a single low-frequency active sonar loudspeaker can be as loud as a twin-engine fighter jet at takeoff.

Noise pollution is an existential threat for Cetaceans

This onslaught of noise has a devastating effect on marine species, especially Cetaceans. This is because they use their keen sense of hearing and vocalizations for almost everything they do. Sonar can displace them from their preferred habitat and disrupt feeding, breeding, nursing, communication, navigation and other behaviors essential to their survival. It can even physically injure them by causing permanent hearing loss, hemorrhages and other kinds of tissue trauma. Shock can drive deep diving marine animals rapidly to the surface or to shore causing strandings or decompression sickness.

Shipping traffic is a major source of noise pollution

in the Ocean.

Image: pixabay.com

Diagram explaining how military grade

sonar devices affect Cetaceans.

Image: strangesounds.org

Whale songs are changing

Cetaceans have an unmatched ability to continue to surprise and mystify us. Their remarkable intelligence equips them with an adaptability akin to our own. This is perfectly demonstrated by the fact that researchers have now realized that, since at least the 1960s, some whale’s calls have been getting lower in frequency, downshifting three white keys on a piano in the case of the Antarctic Blue whale population. This change is almost certainly a reaction to human activity. There are multiple theories as to why exactly this lowering in frequency is taking place among geographically and biologically separate species and populations. One likely answer is that the whales are having to adjust their calls to compensate for anthropogenic noise pollution.

Another more positive interpretation is that whale populations may be rebounding since the end of commercial whaling. At the start of the 20th century there were an estimated 239 000 Antarctic blue whales in the Southern Ocean. Decades of commercial whaling had decreased the population in the region to a mere 360 by the early 1970s. Since protection of the subspecies began in 1966, that number has begun to increase. Scientists speculate that the whale’s anatomy ensures that the louder their calls get, the higher their pitch becomes. As the population grows, meaning more whales per square mile, the whales may be decreasing their volume because they are more likely to be communicating over short distances. In other words, the whales calls may be lower-toned today simply because they no longer need to shout to each other over such vast distances.

No matter what the reason for these changes, two things are clear. We now hold the fate of countless species in our hands and currently, we are failing in our sacred and self-created role as stewards of this planet.